This play is so rich in conflicts and questions that rock the human psyche, it is difficult to know where to start. Ibsen makes life easier for his audience with clear symbolic imagery to schematise the tension that racks the mind of Ellida, the lighthouse keeper’s daughter known as The Lady from the Sea. This is only the second Ibsen play I have seen on stage, but already I can see that a feature that marks him out as a great dramatist is his talent for psychological insight. In his plays one detects the enlightened spirit with which Freud determined to apply psychoanalysis as an effective therapy for the mind; it comes as little surprise to note that these two men were more or less contemporaries (Ibsen was 28 years Freud’s elder).

The symbolic tension comes from the contrast between land and sea. Having been born on the precipice between the two, Ellida is drawn from her confining paradise by the allure of the sea. Her first love came at the age of sixteen shortly after the death of her mother. She fell in love with a fugitive sailor who made her promise to wait for him until he comes to claim. The man is a murderer and a manipulator, but this is not what Ellida sees. She sees the seduction of the unknown, the excitement of unlimited and undefined potential. The life laid out before her stands in stark contrast to the life offered by the land-based doctor (Wangel) she eventually marries. He offers her leisure, prosperity and a life happier than anything that the sailor could offer …probably. And it is that nagging uncertainty held by the mysterious sailor that has tortured Ellida for a period of time longer than her entire life before that youthful encounter. The poor, sympathetic doctor has laid out his cards on the table. He’s made an offer, a very good offer, but what cards does ‘the man from the sea’ hold to his chest, as he sends Ellida letters from exotic locations around the world?

It is telling that Ellida meets Wangel after her father dies. The psychoanalyst might deduce that in the earlier case the ‘patient’ (Ellida) sought in the sailor someone to replace the tender affection that her mother gave her, but in the later match it was the grounded stability and comfort that Dr Wangel was able to provide when she had lost her lighthouse father. What the doctor could not provide was a connection to the sea so essential to her being. A third loss (of a nature apparently not uncommon in Ibsen) is that of Ellida and Dr Wangel’s child together. There’s nothing in the life that Wangel provides her that can fill this void, and therein lies the all too real tragedy of Ellida’s relationship to Wangel. He copes by skirting over the issue, seeing life’s pleasure and blocking out the unsavoury part, and he is allowed to respond in this way by his work. The therapist’s diagnosis might seem insufferably neat, but it must be remembered that the symbolic framework of this play is the architecture which allows a deeper examination of its characters.

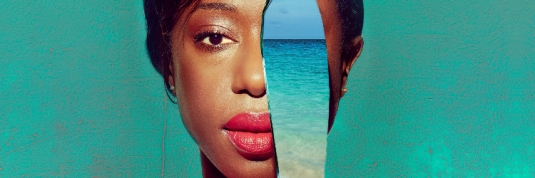

It is in these circumstances that the play takes place. And so from here I will contextualise my reflections within the specific production at the Donmar Warehouse last night. The very first thing we see on stage is Ballestred painting a picture of a mermaid – appropriate for a play first seen in Copenhagen, but also for a woman who never really left her roots by the sea. More symbolism! But from the character Ballestred also there emerges a symbol for a dichotomy prevalent in this play. He is a dilettante who flits between different modes of expression without finding a vocation. In a way he lives the freedom that Ellida craves. He’s not defined in any particular way. Ellida however is a doctor’s (second) wife and a distant stepmother to two teenage girls. That freedom is attractive but carries with it the taint that one might forgo maximising their potential in one discipline. It is Ballestred’s Jamaican accent, along with the onstage lagoon, that places our story not in the fjords of Norway but a Caribbean island. If one is to seek a new location for Ibsen’s play, this is about as appropriate as you are likely to get. Talk of paradise easily evokes palm trees and beaches. And the sea that symbolises an escape for Ellida is paradoxically also that which traps her in her pleasant but stifling existence. Perhaps the only slight flaw in this relocation is that the removal from the sea that afflicts the Norwegian Ellida, cannot apply (at least physically) to the Caribbean Ellida.

On seeing Ballestred’s painting, Lyngstrad, a sculptor who actively seeks self-definition as a tortured artist, is only too happy to weigh in with his comments on the art of an amateur. He questions the doomed back story of the mermaid restrained from returning to the sea (more symbolism!). Lyngstrand is a tragic character, as is so brutally surmised by the Wangel daughter, Bolette, for whom he harbours an unrequited love: she expresses relief that the sickly boy may not reach his thirties because he will always be disappointed in his hope that artistic success and fame is but around the corner, despite knowing deep down that he’s simply not very good. Given the tragedy of his character it is a shame, cruel even, that he is in this production the silly comic relief of the play. His pairing with Bolette’s sister Hilde by the end of the play (I’m not sure how much of this relationship is taken from the original) is the happily-ever-after ending that cannot ring true for his character. In fact we know from The Master Builder that Hilde’s future lies beyond Lyngstrand.

More comedy is found in his perverse view of marriage as a transferral of the powers of the husband to the lesser capabilities of the wife. He redeems himself slightly by revering his mother above his father. While the view Lyngstrad posits is ridiculous, there lies within it a truth, or rather questions that may apply to Ellida: has she adopted the reckless traits of her first lover? What of Wangel’s first wife is evident in his own present day character? Should Ellida submit to the example that her husband sets? Can Wangel learn to understand his second wife? It hints at the tension that derives from the union in marriage between two individuals with two separate pasts. It problematises the whole institution of marriage in general. And so it is fitting that in the end of the play Wangel and Ellida discard their wedding bands in the sea, where lies abandoned the promise Ellida submitted to the sailor.

With all the above in mind I shall attempt to treat with an even hand the relationship between Bolette and her one time tutor Arnholm, a figure who bridges the generational gap between Ellida’s love triangle and the youthful Bolettes, Hildes and Lyngstrands, who are still finding out who they are. In Bolette we recognise Ellida’s yearning for freedom. She feels trapped by the death of her mother, the guilt of abandoning her father. Rather than Ellida, it is Bolette who has taken over the void left by Wangel’s first wife; she is the one who looks after the house, leaving Ellida all the time she needs to wallow in her self-doubt. While Ellida sought in a man something to fill the void her mother left, Bolette attempts to fill it herself, and ties herself down in the process. Along comes Arnholm, back with a limp from military duty, to save the day. His attraction to Bolette is reminiscent of Gaston and Gigi (‘thank heaven, for little girls’, etc.). But to take the relationship as intended by its author, I think one ought to refrain from shining a contemporary light on the seventeen-year age-difference.

The acting in this performance was good throughout, but I was bothered throughout by unidiomatic delivery of a few lines. There was the odd moment where lines were spilled out in a most unnatural way, as if the actor was ticking off the words, mentally assuring themselves that they didn’t miss out any. The three I have in mind in particular are Jonny Holden (Lyngstrand), Tom McKay (Arnholme) and Finbar Lynch (Wangel). For the most part thought I thought these particular performances were good not great. Arholme could have had more dignified gravitas, befitting a returning war veteran with a passion for learning. He didn’t strike me as one hitting 40. Wangel was endowed with a beautiful, reassuring speaking voice. For me there could have been more of an air of preoccupation, and the feigned jollity didn’t come across as natural (perhaps it shouldn’t have, but that aspect didn’t ring true). Lyngstrand’s performance was overly petulant. I get that he is a wannabe, but that would have remained clear from a subtler performance.

The two daughters were both well-performed. Bolette (Helena Wilson) was quietly compassionate and thoughtful, though signs of her attraction to Arnholme weren’t so detectable, which made his proposal come across as surprising, and her acceptance more so. I feel that to an extent this relationship suffered from an uneasiness surrounding the relative ages of these paramours; perhaps that had to be the case given the relocation of the play in 1950s Caribbean. If Lyngstrand was the comic relief, Hilde (Ellie Bamber) was his support act. She came across as frivolous and distrustful, but also light and care-free. The relationship with Lyngstrand came across as too neat and therefore unsatisfactory. Perhaps they didn’t have enough time together to build complexity. Basically I wasn’t too sure about the part that Hilde was playing, but she played it well.

Ballestred (Jim Findley) was charming and the cast was reliant on him to remind the audience we were in the Caribbean! An easy, enjoyable turn in a small part. The other smaller part, though his character loomed large, was the enigmatic, homicidal sailor. He entered the scene dripping in sand and water. He didn’t give too much away, yet at the same time didn’t come across as aloof or even excessively arrogant – the performance was a good fit. He clashed so awkwardly with Wangel, which I think is how it should be.

Nikki Amuka-Bird as Ellida rose to the challenge of leading this cast. Throughout she drew the eye, playing well the turmoil veiled in cheeriness. I wasn’t fully convinced of her relationship with Wangel, but his admirable selflessness in the face of Ellida’s irrationality makes her decision at the end of the play understandable. The main part shone as a main part should. All in all, I rated this a good production of a great play.